Unique ossuary inscribed with the rare New Testament spelling Ζαχαρίας (‘Zechariah’), decorated on all four sides with exceptional motifs: Temple columns, rosette, hovering winged figure, crescents, swastika-meander, and amphora, suggesting priestly status and plausibly identified with Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist

Site item id

19115

Collection name

Item period

The Zacharias Ossuary

Introduction

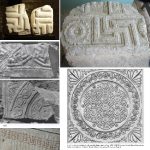

The ossuary of Ζαχαρίας (= Zechariah) is unique in its features and decoration. It differs from the overwhelming majority of the thousands of Jewish ossuaries from the late Second Temple period discovered in Jerusalem and its immediate surroundings. It is unique in its style of ornamentation, in the artistic motifs on its four sides, in its symbolism, and in its inscription. The ossuary is dated to the first half of the first century CE. As far as is known, it was discovered in East Jerusalem or nearby.

The ossuary was purchased from the licensed antiquities dealer Kamal Imam of East Jerusalem several decades ago. It is part of the largest and most important private ossuary collection in the world and was displayed in two international exhibitions in the USA in 2024 and 2025.

While most ossuaries served as “containers” for keeping the bones of Jews interred within them, and were placed in niches or adjacent to the walls of family burial caves, the ossuary of Zechariah seems to have been intended for something beyond that: a memorial monument, designed to be prominently displayed, and to embody within the deceased’s community the memory of a known and respected figure, perhaps a saint, who was regarded as one enjoying divine connection and protection.

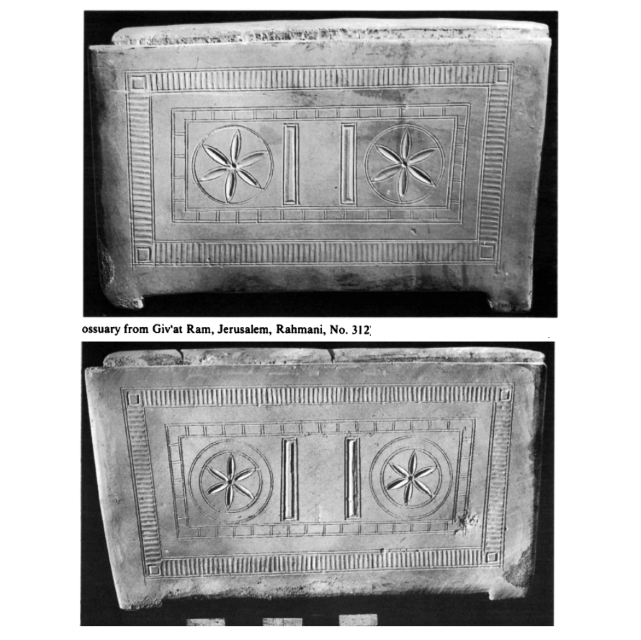

Decoration on all four sides of the ossuary

The vast majority of ossuaries from the Second Temple period were either completely undecorated, or decorated only on one side, usually with rosettes or geometric motifs. Since ossuaries were placed near walls in burial caves, or inside niches, multi-sided decoration was unnecessary.

In contrast, the ossuary of Zechariah is richly decorated on all four of its sides. This strongly indicates that it was intended to be viewed from different angles, and that it was likely placed (or meant to be placed) in a central visible location within the burial chamber, or in a hall elsewhere, where its sides could be seen in daylight. Such a display suggests a desire to preserve a public memory, beyond private family remembrance, and indicates that the person whose bones were interred in the ossuary was an individual of extraordinary communal and/or religious importance (possibly a saint).

Art and technique

The decoration of the ossuary was executed with great precision and exceptional symmetry by a professional artisan. Unlike most ossuaries, where designs were carved deeply into the stone, here the decoration was created by shallow incisions using a ruler and compass, then filled with brown pigment. This technique, extremely rare in the ossuary corpus, creates a strong contrast with the light surface of the limestone from which the ossuary was made.

The investment in decorations covering all four sides of the ossuary confirms that it was a special commission. Its production required careful planning and significant expense - again, a clue to the special status of the deceased in his community.

The Iconographic Program

The ossuary presents a set of unique motifs. Instead of repeating common patterns, it combines rare or unique symbols, connected in one way or another to the deceased and the story of his life as known among his community.

- A floating body (object) inside a rectangular frame

One broad side of the ossuary shows a schematic rectangular structure (similar to the way architects still schematically depict buildings today). The structure has openings in its roof, walls, and base. At the center of the structure “floats” a semi-circular form, in a unique design.

The motif of a floating form within a building has no parallel in any other ossuary decorations (or on any other ancient architectural element). The floating form may symbolize the “wings of the Shekhinah” - the divine presence (“Holy Spirit”) described in Ruth 2:12, or the wings of an angel. Since Jewish tradition forbade artistic representation of God, this image provided a symbolic means to depict divine presence, in the sense of God granting protection and shelter to the deceased. The connection between the image of God and wings or a bird (dove) is well known from the ancient Near East and particularly prominent among Jews of the first century. In the New Testament it is told that at the baptism of Jesus (a Jew) in the Jordan, the Holy Spirit appeared to him in the form of a dove: “And Jesus went up immediately from the water, and behold, the heavens were opened to him, and the Spirit of God descended upon him in the form of a dove. And a voice from the heavens said: This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased.” (Matthew 3:16–17; also Mark 1:10–11; Luke 3:21–22).

The structure can be identified, based on other motifs on the ossuary, with the House of Yahweh in Jerusalem (the Temple). These motifs include the two columns that stood at the entrance of the Temple, the meander motif (on the other long side) known from Herod’s Temple complex in Jerusalem, and the amphora, which was a sacred vessel for libations of wine and oil in the Temple.

The schematic plan of the building on the ossuary (a double rectangle with openings) differs from all previously known schematic building motifs on ossuaries - those are shown as closed rectangular frames, whereas on the ossuary of Zechariah the structure (the Temple) has openings in all directions. These openings were evidently intended to allow the Holy Spirit to enter and exit the sanctuary freely, also hinting at the meaning of the floating object inside.

Alternative interpretations proposed for the floating object, such as crown, shofar, or jewel, are not plausible and lack any parallel.

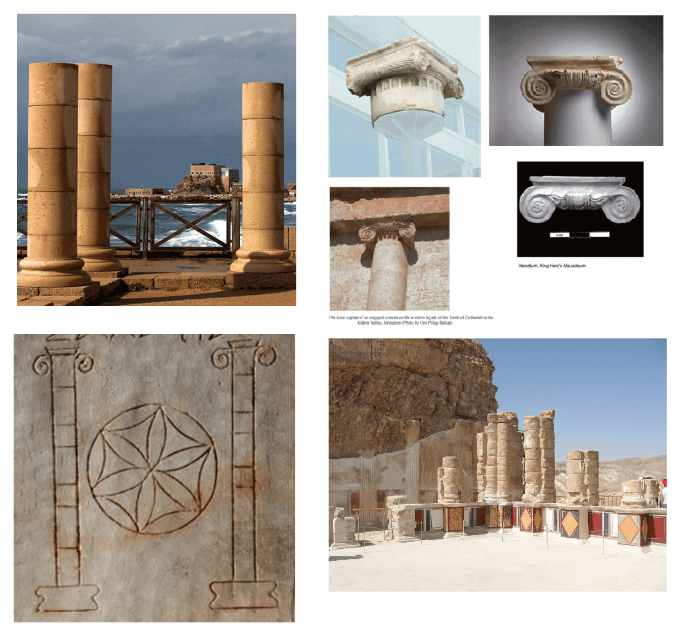

- Columns and Ionic capitals with a rosette

On one narrow side appear two tall columns, composed of multiple drum segments, with bases and Ionic capitals. Between the two columns is set a six-petal rosette, a common symbol on Jewish ossuaries (rosettes were the most accepted Jewish symbol on ossuaries).

Multi-drum columns are known from Herodian monumental architecture at Caesarea, Masada, and Herodium - monumental projects built by King Herod, who also rebuilt the Temple in Jerusalem. The free-standing placement of the columns in the façade recalls the two columns of Solomon’s Temple (Jachin and Boaz) and those who stood in front of the second Temple.

Decoration of the Temple façade with columns and other motifs links the deceased to service in the Jerusalem Temple, suggesting that the deceased was a priest.

- The amphora (jar with two handles

The opposite narrow side of the ossuary is decorated with a large amphora. Jars and amphorae are known from a limited number of ossuaries and also from Jewish coins from the Hasmonean period until the Great Revolt (70 CE). The amphora was a sacred vessel for libations of wine and oil in the Temple, and therefore symbolized Temple worship and purity. Pau Figueras – in his classic book on decorated ossuaries, he suggested that the amphorae represent vessels containing wine or oil used in the Temple. It was one of the most legitimate and charged symbols of Temple service. The amphora motif, usually with two handles, also appears on several ossuaries and on "Darom" (South) oil lamps from Judea in the late first century AD. Scholars, including Prof. Rachel Hachlili, have suggested that the amphora symbolized not only a Temple vessel but also eternal life or resurrection. Wine and oil were considered “living” liquids, and the amphora with its open mouth was seen as a mediating vessel between the world of the living and the world of the dead.

Two amphorae also decorate the stone table that stood at the center of the synagogue at Magdala (on the shore of the Sea of Galilee) from the first century CE, flanking a seven-branched menorah. In early Christian communities, the amphora or vase also became a Christian symbol, appearing in several church mosaic floors from the fifth and sixth centuries CE in the Land of Israel and its surroundings, with branches, tendrils, and grape clusters emerging from it. It is possible that the vase motif reminded or symbolized to Christian believers the cup held by Jesus at the Last Supper, later called the “Holy Grail.”

Two amphorae also decorate the stone table that stood at the center of the synagogue at Magdala (on the shore of the Sea of Galilee) from the first century CE, flanking a seven-branched menorah. In early Christian communities, the amphora or vase also became a Christian symbol, appearing in several church mosaic floors from the fifth and sixth centuries CE in the Land of Israel and its surroundings, with branches, tendrils, and grape clusters emerging from it. It is possible that the vase motif reminded or symbolized to Christian believers the cup held by Jesus at the Last Supper, later called the “Holy Grail.”

- Geometric meander motif and two crescents

The other broad side of the ossuary shows, in its upper section, a continuous geometric motif (meander) resembling swastika-like interlinked shapes, above two crescents. This meander motif is known from stones of the Temple complex built by King Herod, discovered in the Temple Mount excavations, and is not known from elsewhere (see photos).

The motif of the two crescents is exceptional: in Judaism, the moon represents renewal, cyclical time, and resurrection (see the blessing of the moon). The doubled motif likely reinforced the theme of resurrection and hope. In the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Hullin, it is said that the renewal of the moon each month symbolizes the Jewish people: just as the moon wanes and renews itself each month, so too does the Jewish people experience cycles of decline and renewal. It should also be noted that the Jewish calendar is lunar, based on the moon’s phases, and that the “Blessing of the Moon” was common among Jews in the Roman period, recited in the first half of the Hebrew month, facing the waxing moon, blessing Yahweh “who commanded the moon to renew itself.”

The inscription: Ζαχαρίας ( Zacharias in Greek)

The ossuary bears a carefully engraved inscription in Greek: Ζαχαρίας (“Zechariah”).

The inscription was carved with precision, by a professional stone engraver, likely in the workshop where the ossuary itself was made. This is unlike most inscriptions on ossuaries, which were hastily scratched inside dark burial caves, usually after bones had already been placed inside. Fewer than 2% of ossuaries contain pre-planned, carefully executed inscriptions, indicating the importance of the deceased within his community or family.

The inscription contains only a single name, unlike most ossuary inscriptions that give the name of the deceased and his father, which suggests that the deceased was so well-known that his personal name alone sufficed.

The use of Greek appears to have been common among the Jewish-Christian group in Jerusalem in the years before the destruction of the city. The New Testament itself was written in Koine Greek, the common dialect of Greek that was widely used across the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East from roughly 300 BCE to 300 CE, and not in Aramaic (the language Jesus likely spoke and taught). This indicates that Greek served not only outward communication but also internal discourse among believers.

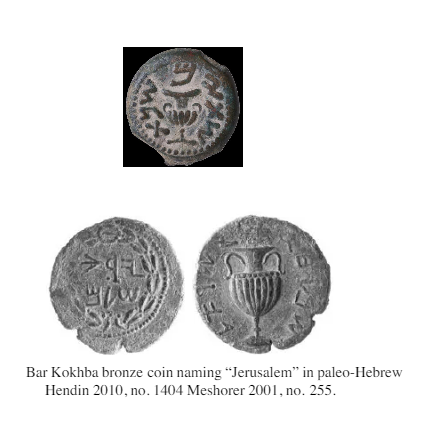

Statistical rarity of the name “Zechariah” or “Zacharias – Ζαχαρίας”

Of about 1,100 inscribed ossuaries published to date (by Rahmani, and in the full corpus of inscribed ossuaries published by Cotton and others), the name Zechariah appears only four times: twice in Hebrew and twice in Greek. By contrast, common male names such as Simon (73), Joseph (68), Judah (61), Eleazar (33), Jesus (29), John (25), and Hananiah (26) occur much more frequently, indicating the relative rarity of this name. Its rarity increases the significance of its appearance here, especially in the precise New Testament form Ζαχαρίας. This strongly supports the likelihood that the ossuary commemorated a recognizable historical figure.

Moreover, one of the most striking epigraphic features of this ossuary is the exact spelling of the inscribed name. The form Ζαχαρίας appears here precisely as it does in the Greek New Testament. There, this name consistently refers to Zechariah the priest, father of John the Baptist.

This is, as far as current knowledge, the only archaeological find in which the name appears in this exact form. In all other epigraphic occurrences, including ossuaries, inscriptions, and documentary sources, the Greek name Zechariah is written in variant forms, usually Ζαχαρίου, or with other endings and spellings. This discrepancy is not trivial: the exact spelling Ζαχαρίας reflects a specific literary and linguistic tradition, associated with early Christian texts.

The uniqueness of the spelling adds powerful weight to the identification. Not only is the name itself relatively rare in the ossuary corpus, but its exact New Testament form appears here uniquely, combined with an exceptional “memorial” ossuary. The combination greatly strengthens the hypothesis that the ossuary commemorated that very priest, Zechariah the priest, mentioned in early Christian tradition.

Personalized and symbolic design

Unlike general ossuaries decorated only with rosettes and geometric motifs, the motifs of this ossuary are personalized:

- Priestly service in the Jerusalem Temple: Columns recalling the Temple, a geometric motif from the Temple complex, a libation vessel (amphora).

- Divine presence: The “wings of the Shekhinah” (Holy Spirit) hovering and protecting the deceased.

- Jewish identity: The rosette.

- Eschatological hope: Hope for eternal life or resurrection (crescents and amphora).

These symbolic motifs suggest, or at least hint, that the interred was a priest of the Temple, whose identity and story were well known in the community and likely throughout the land. According to tradition, the divine favor granted to Zechariah the priest and his encounter with the angel Gabriel were indeed known throughout the country (“And all these things were reported throughout the hill country of Judea,” Luke 1:65).

Historical correspondences

Zechariah the priest is said to have been a relative of Jesus and the husband of Elizabeth, herself a daughter of a priestly family and relative of Mary, the mother of Jesus. According to the Gospel of Luke, Zechariah was a priest from the division of Abijah, one of the distinguished priestly divisions serving in the Second Temple during the reign of Herod. It is told that while burning incense in the Temple, the angel appeared before Zechariah the priest and announced that he would have a son to be named “John,” who would herald the coming of the Messiah (Luke 1:12–17). The vision of the angel (Gabriel) to Zechariah the priest, father of John the Baptist, is one of the central stories of the New Testament Gospels. The story of Zechariah the priest, father of John the Baptist, is told in three of the four Gospels. According to tradition, Zechariah the priest was murdered in the Temple courtyard.

Conclusion

The ossuary of Zechariah is unique within the corpus of Jewish ossuaries: decorated on all its sides with exceptional elements, bearing a Greek inscription with a single (and quite rare) name, and combining a variety of symbols connected to the Temple and priesthood, unusual divine presence, and hope for resurrection.

All the evidence points to the ossuary belonging to a priest of the Jerusalem Temple, of extraordinary standing, revered in his community. A priest probably regarded as a saint among his people, and the ossuary was likely intended not only to preserve his bones but also to serve as an exceptional kind of “monument” to the man.

Of special importance is the spelling of the inscription in Greek: the form Ζαχαρίας appears here exactly as the name of Zechariah the priest appears in Greek in the New Testament, whereas all other finds mentioning “Zechariah” in Greek use different spellings. The unique combination of archaeological and textual evidence strongly increases the probability that the ossuary indeed commemorated Zechariah the priest, father of John the Baptist. Although absolute certainty is impossible, the convergence of epigraphic, artistic, and historical evidence makes this identification highly plausible.